by Abdul Karim Hekmat

Zainullah Naseri has been in Afghanistan three weeks when the Taliban find him. They stop the car in which he is travelling and find in his pockets his Australian driver’s licence – a memento of the country that on the night of August 26 made him the first Hazara to be forcibly deported back to the country he was fleeing.

The six Taliban also find Zainullah’s iPhone, but he pretends it is not working. They do not believe him. Zainullah is punched and kicked. “They told me they would kill me if I didn’t open it.”

The Taliban bundle him into a car and after 20 minutes’ driving, take him to a mud house ringed by high walls. They beat him with wet rods cut fresh from a tree, demanding he open his phone. Again they threaten to kill him. Zainullah relents and offers his PIN.

Immediately, they are scrolling through pictures: the Opera House, the Harbour Bridge, a video of the new year he recorded in 2014. Speaking in broken Dari, the Taliban tell him, “You from an infidel country.” They mean Australia. “You infidel. We kill you. Why you come to Afghanistan? You a spy.”

On the day of his deportation, he was asked repeatedly to return to Afghanistan. “A person talked so much, it was as if there was a wasp on my mind.”

He tells them the truth: he was deported after his refugee application was rejected. But they do not believe him. He is laid out on the ground and again is beaten. “I swear to God, I was deported from Australia,” he pleads. “I don’t live there anymore.” The six men do not relent. “They kept bashing me,” Zainullah remembers.

The Taliban tortured him for two days. He begged for mercy and his life. They gave him five days to arrange a payment of $300,000, threatening otherwise to decapitate him.

Not able to afford food or accommodation in the three weeks since he had been back in Afghanistan, he counted down his days, remembering what he told the Australian government. “I told them 100 times not to deport me. I would be killed. But they did not believe me.”

Zainullah imagined his own death. “Although I was scared, I did not care too much if I die after all this,” he tells me. “There was one thing in my mind: I wanted to see my wife and daughter. I did not see my daughter because I was in an Australian camp when she was born.”

Feeling scared

I first met Zainullah four weeks ago in Kabul, two weeks after he was deported from Australia and a week before he was abducted. I met him in one of the busiest places in Kabul, Kote Sangi, metres from where hundreds of Afghan addicts, smoking heroin, huddle under Pul-e-Sukhta bridge, most of them former refugees who were deported from Iran and Europe. Laila Haidari, who runs a “mother’s camp” for addicts in Kabul, told me “about 90 per cent of addicts are deportees”.

Zainullah looked disoriented and very sad. When I told him that I came from Sydney – I arrived in Kabul a day after he did – his face flickered with excitement. This soon died down, however, once he realised I could not help him go back. He told me that he was staying in a guesthouse in Kote Sangi, sharing a room with many other travellers, mostly Pashtuns, who come from other provinces. “I feel scared there. Who knows, a Talib may be among them, but I don’t have money to pay for a separate room.”

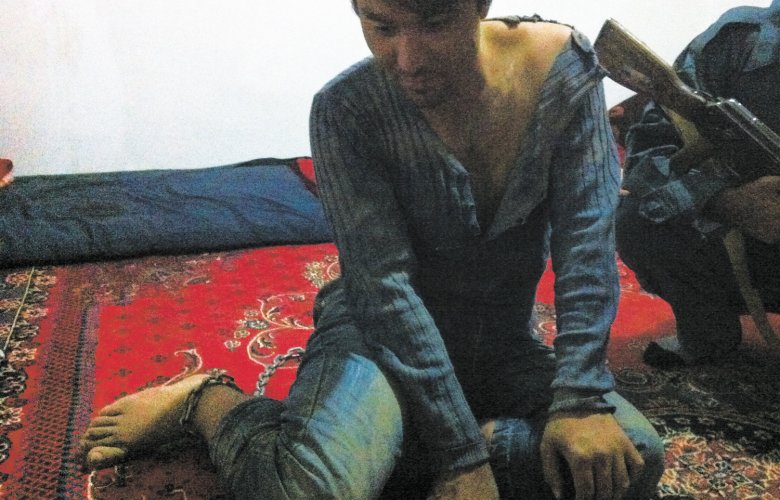

After the first meeting, I lost contact for a few days – his mobile phone was switched off. A week later, I got a call from him with a different number, telling me that he had been captured on the way to his home town. We met again and I looked on in disbelief as he showed me the lash marks on his back and a photo and video taken at the police station where he sought refuge following his escape from his Taliban captors.

Hellish escape

It was thoughts of his daughter that prompted Zainullah to break out. On the second night in captivity, at 10pm, he heard gunfire in the valley. He saw that the Taliban had gone out to fight and locked the gate. He realised it was an opportunity to escape but his feet were chained together. He groped in the darkness, found a rock, and brought it down onto the chain every time he heard gunfire.

At the back of the house, steps led up to a traditional Afghan squat toilet system, a hole above a chamber below. Having broken his chain, he ran for the toilet and dropped into the excrement. The human waste is collected for fertiliser, accessible with a shovel from outside the house’s wall through a hatchway. Zainullah wriggled out through the hatch. For eight hours, covered in faeces, he walked through darkness and early morning. At some point, exhausted, he heard more gunfire – the whizzing of bullets as they passed his ear.

A video captured by Afghan police shows officers firing on him, suspecting him to be a suicide bomber. A voice calling “help” is heard in the darkness. Moments later, three police speaking in Hazaragi are shown in the video, saying in angry voices, “Who are you?” and “Raise your hands”.

You can hear the chain clanking on one of Zainullah’s feet as he staggers on a gravel surface, his arms raised and his shirt ripped at the shoulder. He is being escorted by police now, and asks in a trembling voice, “Where is this?” A soldier answers him: “This is the police station.” Another shouts: “Here is the police station – shut your mouth.”

He was taken to the assistant commander of the area, Abdul Gorgee, where he was interrogated in a closet-sized room. More video shows him still tangled up with a chain. The assistant commander asked him where he came from and what happened to him. He explains in the video that he had been deported from Australia and was captured by the Taliban on the way to Jaghori, his district.

“Why you did not stop?” the commander asks.

“I was scared,” he answers.

“Our soldiers could have killed you,” the commander says, swearing at him.

“Life is too bitter,” Zainullah answers, putting his head down. “It would have been better if they had killed me.”

After a short interrogation, the commander ordered his soldier to break the chain and take him to a hotel where he could shower.

After two days under the supervision of police in Jaghori, he was released. Instead of going to his home, to the daughter he had never seen and the wife for whom he yearned, he fled in fear back to Kabul by a different route.

‘Not a real risk’

In December 2012, Australia’s Refugee Review Tribunal ruled it was safe for Zainullah to return to Jaghori. This was the beginning of the events that almost ended in a Taliban outpost two weeks ago. A week after Zainullah’s disappearance, an Afghan-Australian named Sayed Habib Musawi was killed in the same area. But the tribunal had asserted in Zainullah’s case that “there is a significant population living in Jaghori. His family are living there … [and] as there is a route from Kabul to Jaghori that is secure, there is not a real risk the applicant will suffer significant harm.”

Zainullah is from Ghazni province, the most volatile and dangerous province in Afghanistan at the moment. Of its 22 districts, 18 are very insecure, including Jaghori. In recent weeks, Islamic State supporters have penetrated into Ghazni and in some areas IS flags have been raised.

Since last Thursday, the Afghan government has been engaged in fierce battle with the Taliban and the IS in Ajristan, a district bordering Uruzgan province, where Australian troops were based. The insurgents associated with the IS have decapitated 11 innocent men and women in that district and driven many people into the mountains. General Qasimi, a Hazara parliamentarian who survived a recent assassination attempt near his home in Kabul, told me “at least two or three Hazaras are killed in Ghazni province every week by the Taliban”.

Mohammad Musa Mahmodi, the executive director of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, said: “It’s totally unacceptable to return a refugee to Afghanistan in this critical moment. It contradicts their [Australian] own law not to deport refugees where they face danger.”

Asked about Zainullah’s case and whether any attempt had been made to assess the ongoing safety of deported asylum seekers, a spokesperson for Immigration Minister Scott Morrison said: “People who have exhausted all outstanding avenues to remain in Australia and have no lawful basis to remain are expected to depart.”

Depressed and alone

Zainullah’s capture and torture is one thing, but he also grapples with the fact nobody will believe he was deported from Australia. “You must have committed a crime in Australia,” Afghans told him when he returned. “They don’t deport refugees.” He denied the accusation, but nobody believed him, including his family.

When he arrived in Kabul on August 27, he went to see a GP – there are no psychologists – about the depression and anxiety he developed during the nearly three years spent on a bridging visa and in detention centres in Australia. It had become worse in the lead-up to his deportation. He couldn’t sleep for five consecutive days: two in Villawood, and three more on the way to and in Kabul.

In a letter addressed to Morrison before Zainullah was forcibly deported, forensic psychologist Kris North wrote that Zainullah had symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder that “will deteriorate further if he is returned to Afghanistan” given “he will not get proper psychological help” there.

Zainullah has had a long walk to find protection. As a Hazara, a long-persecuted minority in Afghanistan, he fled and spent nine years in Iran as a refugee but was deported back in 2011. After staying in Afghanistan for another two months, and getting married, he again felt unsafe. This time, he decided to go to a place where he would not be deported.

It took him six months to get to Australia, including 12 days on a boat. “We nearly lost our lives,” he says. “I wish I would have died then, than to suffer like this. It’s very hard.” After six months in detention on Christmas Island and at the Curtin centre, he was released into the community on a bridging visa that allowed him to work. He soon found a job, working as a professional tiler for a year after getting his licence and buying a car and tools.

But in August 2012, Zainullah’s refugee application was rejected by the Immigration Department. Four months later, he was rejected again by the Refugee Review Tribunal on the grounds that Jaghori was safe. He made further applications until, in January this year, a one-page letter came from Morrison’s department: “As you have no further matters before the department, you are expected to leave as soon as practical.”

For seven months, he attended a monthly appointment where he was asked to leave the country and each time refused. In August, he thought he would refuse again. He took his mobile and a wallet and parked his car under a shopping centre in Auburn without realising he would never come back. At the interview, his case manager pressured him either to return voluntarily to Afghanistan or be taken to Villawood. He rejected both. He pleaded with his case officer not to take him into detention. “I cried a lot and asked, ‘Please, please don’t take me to the detention centre. I have been there before. I don’t want to be deported.’?”

On the day of his deportation, about 10am, he was transferred to a solitary room where he was asked repeatedly to return to Afghanistan. “A person talked so much, it was as if there was a wasp on my mind.” That night, he was taken to Sydney airport. He and six department escorts boarded the plane from a different door, away from other passengers’ eyes. “I did not know where I was. I did not sleep for two nights. My mind was not working. I just knew that my world is going to end.”

The Afghan embassy in Canberra didn’t issue a passport for Zainullah, disagreeing with his forced removal from Australia. Instead, the Australian government issued a travel document bearing his name and photo, but not his signature. The document was carried by his escorts, who showed it at every checkpoint. He was given a photocopy.

Walking alongside me, he shakes his head. “I ask why the Australian government wasted my time for so long. Made me wonder for three years. Then they dump me here. I have no future now.”

On the dirt roads of Kabul, he looks at the scars of war on the buildings, the open sewers smelling like rotten meat, and female beggars in burqas stretching out their hands, asking for money. We reach the fourth-floor restaurant where we first met, and I asked him about his future. “I don’t know. I can’t go back to my home town,” he tells me, rubbing his chin nervously. “I feel like jumping from here, or ending up living with those addicts under the bridge, if I stay in Kabul.”