STUDY OF THE IMPORTANCE OF IMPROVING THE COMMUNITY SECURITY OF MARGINALIZED GROUPS IN PEACEBUILDING EFFORTS IN NON-WESTERN SOCIETIES

By Annika Frantzell

Department of Political Science

Master’s Thesis in Global Studies

Supervisor: Ted Svensson

Lund University

Abstract

This thesis is focused on the lack of investment in the human security of the marginalized Hazara minority of Afghanistan. Human security is a relatively new concept over which there is considerable debate and this thesis presents a discussion of various debates regarding human security and peacekeeping before taking a firm stance in the debates, emphasizing the importance of investing in the human security of marginalized groups in non-Western societies. The case of the human security of the Hazara has never been researched before and this thesis therefore represents a unique case study. This thesis finds that there are four clearly identifiable factors which have led to a lack of investment in the Hazara, namely: the inaccessibility of their native region, the Hazarajat, continued discrimination against them, the militarization of aid, and the top-down, donor-driven nature of aid in Afghanistan. The effects of this lack of investment manifest themselves both domestically within Afghanistan and internationally, with thousands of Hazaras emigrating to other countries, which emphasize the importance of a bottom-up human security approach to peacebuilding which involves an understanding of the socio-political situation on the ground.

Introduction

What happens to the Hazara is “not just the story of this people. It’s the story of the whole country. It’s everybody’s story.”

Dan Terry, American aid worker in Afghanistan, 1946 – 20101

The North American Treaty Organization (NATO) led an invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 with the goal of overthrowing the Taliban and denying al-Qaeda a safe haven in the country which was quickly deemed a success. Ten years later, however, Afghanistan finds itself battling a resurgent Taliban while trying to develop a historically poor country rendered even poorer after decades of conflict. Following the perceived defeat of the Taliban in the months following the October 2001 invasion, billions of dollars of aid began pouring into the country from around the world in a bid to bring peace and development. Efforts at peacebuilding and development in Afghanistan have been widely criticized despite the increased importance of these efforts in the face of the impending withdrawal of foreign troops in 2014, with particular criticism being leveled at the role of NATO forces in providing aid to Afghan citizens in a bid to win hearts and minds away from the Taliban. Critics of these peacebuilding efforts argue that national security is being promoted too much to the detriment of the human security of the Afghan people, which should be the focal point of peacebuilding and development efforts.

Human security is a relatively new concept in the field of security studies which shifts the focus of security from states to people. Afghanistan presents a prime example for examining the implementation of national security, human security, and peacebuilding measures as the situation in which the country finds itself, not quite post-conflict but not precisely in fully fledged conflict either, seemingly blurs the lines between these concepts as simultaneous efforts are being made to secure the country from the threat of insurgency and improve the human security of its citizens. Human security is the subject of much debate as it is discredited by its critics who consider it somewhat vague and too conceptual in the sense that it is hard to translate into policy while those that support the concept are divided as to its definition and implementation. This thesis grounds itself in these debates and argues in favor of the importance of a bottom-up human security approach in peacebuilding and of dissociating human security from national security with an emphasis upon the importance of improving the human security of marginalized groups, particularly in non-Western societies, by focusing on

the unique and never before studied, as far as the author can determine, case of the Hazara minority of Afghanistan. By using the lack of investment in improving the human security of the Hazara minority as a unique case study, this thesis will illustrate the importance of investing in marginalized groups.

Marginalized groups and the concept of community security, originally proposed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) as a subsection of human security, is rather underemphasized in human security literature and Afghanistan presents a very fitting case study to emphasize the importance of the community security of marginalized groups as the country is divided on racial, ethnic, religious, and gender lines and is thus representative of the larger differences between group-based non-Western and individual-based Western societies. Non- Western, in contrast to Western, countries are commonly viewed from within not as societies consisting of numerous individuals but as societies composed of different communities and

groups whose identities may or may not intersect with one another, which has important implications for peacebuilding in non-Western societies. Understanding a society as consisting of groups instead of individuals leads to an acknowledgement that some groups may be better off than others due to possible factors such as historic discrimination and that marginalized groups, if such exist, should be prioritized in human security-based peacebuilding efforts. As mentioned, this argument will be given empirical weight through the overlooked case of the Hazara. Given the currency of the topic of Afghanistan for the past decade, there is

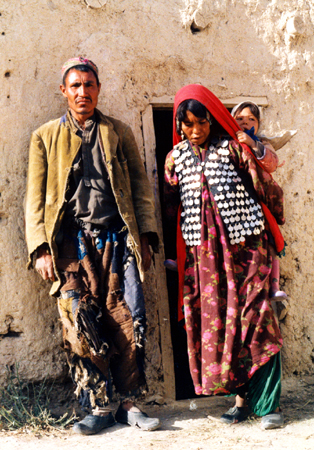

surprisingly little known about the Hazara outside of Afghanistan and the wider Middle East / South Asia region where they are concentrated. They are of particular importance to the peacebuilding efforts in Afghanistan as while the decision to go to war in Afghanistan in response to the September 11th terrorist attacks was widely condemned, the predominantly Shia Muslim Hazara welcomed it as salvation for their people. The Hazara were the targets of ethnic cleansing and brutal treatment by the Sunni Muslim Taliban and in autumn 2001, their fate looked extremely bleak. Persecuted by the Taliban because of their different physical features and religious beliefs, which had served as the weak justification for centuries of discrimination, there seemed to be little hope of deliverance for the Hazara. However, the widely celebrated fall of the Taliban and a constitution guaranteeing equal rights for all minorities opened up a plethora of opportunities for the Hazara which had been unimaginable just a few years earlier.

The turn of the tide was at last in favor of the Hazara, who found themselves promoted to government positions, filling important jobs as NGO employees and translators for NATO forces, and excelling in education in record numbers, leaving other ethnic groups lagging behind. The Hazara were proving to perhaps be the key to the nation’s future by being models for the rest of Afghanistan of what could be achieved if all Afghans embraced education and democracy. However, at the same time as the picture of a triumphant Hazara minority was emerging, another very different picture was also being painted: one of a historically marginalized people facing continued discrimination socially, politically, and economically; of an ignored group whose plight was forcing them to make perilous journeys by land and sea to other countries in search of better lives; of a people whose traditional stereotype as the donkeyslaves of Afghanistan doing them no favors in the new sociopolitical landscape of their country.

What with the scale and duration of the international engagement in Afghanistan and the historic plight of the Hazara and their eagerness to be included in the development of the new Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, the lack of aid money being directed towards them to improve their human security is a puzzling issue. These are a people whose historic homeland, where many of them still reside, has consistently been labeled as being among both the safest and the poorest in Afghanistan and who are exhibiting a thirst for democracy and education, and yet a relatively small amount of aid money has been invested in them. Many Hazara face levels

of such extreme deprivation that they lack access to the most basic of utilities, such as sanitary latrines, potable water, and electricity, and live in areas that lack paved roads. Additionally, Hazaras make up a majority of the Afghan refugees making their way to foreign countries due to a lack of security and opportunities in Afghanistan. They thus have the lowest levels of human security of any ethnic group and an evident drive to improve their standing and yet there is a consistent pattern of aid being diverted to other groups being prioritized on national security grounds.

This thesis is therefore focused on the following two research questions:

Why is there a lack of investment in improving the human security of the

Hazara?

What have the effects of this lack of investment been?

Habibullah

Hi, well described and appreciated for the effort being done.

cheer,

habibi